Digirati

Digirati

Digirati

Digirati

Tom Crane,

Digirati, May 2017

This work is licensed under a

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License

The first part of this series made much of the Presentation API’s avoidance of descriptive metadata. IIIF confines itself to the semantics of presentation, and that gives us interoperability by steering clear of the object’s meaning. Now we can all view objects over the web in whatever viewers, workbench applications, web pages or other user interfaces the IIIF manifests for those objects find themselves in.

Wrapping those objects in meaning and giving them context is where your model comes in. That meaning resides in other places, both formal - a machine readable record conforming to some accepted scheme - and informal - an essay that describes the object in prose.

How does the IIIF presentation of the object (a manifest) relate to other information about the object, such as a MARC record in a library catalogue, or an archival item record, or metadata in a collection management system? How do we find out things like subject, creator, genre or date for an object viewed over the web using IIIF? Your model, your viewpoint on your objects’ relationship with the world, extends beyond the object into a web of connections with other entities such as people, places and events that you have authoritative things to say about. And your objects also have links to content: things that you and others have said about them. Finding aids, curatorial essays, explanatory editorial, educational resources, viewpoints, counternarratives, blog posts, comments, tags, likes and mentions. How does a IIIF manifest fit into all that?

The manifest is an addition to your model, alongside all these things, as a format for the digital surrogate of an object so that you can make it viewable over the web. It doesn’t replace any of the other types of metadata or content. It has mechanisms for linking to all those other things, and there are emerging best practices for how those other things link to it.

Is there a direct relationship between a descriptive metadata record for your object and a IIIF manifest? Not always. Most obviously, you may not have digitised all your objects, so for many records there is nothing to present using IIIF. An un-digitised book cannot usefully be described by IIIF, except in the peculiar case of a manifest of blank canvases that represent views of the object (e.g., pages) that you have no images for. It’s unlikely that you would regularly create a manifest for a book without actually digitising it, because you need a sequence of views (the canvases) each of which has the correct aspect ratio for that view, knowledge that usually comes from photographing pages.

Less obviously, even when the thing described by a catalogue record has been digitised, it might not correspond directly to something that makes sense as a IIIF manifest. Catalogue records do not always equate to something that a human would consider a manageable object, whereas a manifest should, because it’s meant to present something for a human to look at. A MARC record for a printed book might be an obvious descriptive counterpart to an IIIF manifest for viewing that book, but consider these two (real) examples:

The physical artifact is a pencil drawing of the stomachs of a turtle and a shark side by side; on top of this have been glued two smaller drawings, one of a frog’s stomach and one of a snake’s stomach. The three drawings are separately created things, and have each been given their own identifiers in the archival hierarchy - there are three separate records.

There is only one image, because there was only one thing to photograph: the sheet of paper on which the turtle and shark stomachs were drawn and the other two attached. A manifest for each of these three archival records would contain one canvas annotated by the same image in each case. We could use IIIF fragment selectors to crop the image differently in the three cases, but this would hurt the user’s experience of looking at the object. In a viewer, you’d want to see the whole piece of paper, just as you would if your interest in a drawing of a snake’s stomach led you to to the archive in person and you had the sheet in front of you on the table. Although there are three catalogue records, for showing to a human it’s one manifest.

The catalogue record represents the entire publishing history of a periodical over a century; there are hundreds of volumes and thousands of separate issues, occupying many feet of shelf space. The logical coverage for a IIIF manifest would be a single issue, as that is something that a human could hold and read and is something that makes sense in a viewer. But there is no bibliographic record for a single issue, just one for the whole title.

Between these two extremes are multi volume works, boxes of correspondence, sets of photographs and other aggregations of content that may or may not result in a satisfactory user experience as a single manifest, a single sequence of images. For the same reason that publishers and printers would not conspire together to produce a 10,000 page book as a single bound volume, IIIF publishers should aim to produce manifests that client applications can present to a user without overloading the user or themselves with too much content. That doesn’t always align with the “object” described by a catalogue record.

Although the examples are image resources, the same concerns over granularity may apply to AV materials, or even 3D objects. For these, physical scale is not the issue; a Saturn 5 rocket can be perfectly comprehensible as a single object.

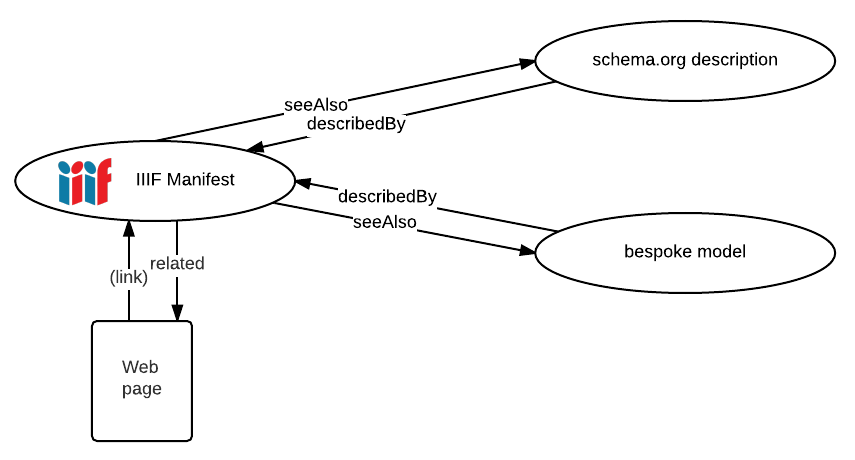

The manifest links to your model using IIIF’s seeAlso property. The manifest publisher can assert one or more links to machine readable semantic metadata, and should provide enough information for a software client to recognise what’s at the other end of the link and decide whether it could consume it or not. This is where you would link to the MARC record, or the catalogue metadata, or a schema.org description, or a Dublin Core description, or an expression of your own model for the object’s semantics. You can link to multiple descriptions. The seeAlso property is where any harvesting agent or software processor of a manifest should look for meaning, to make sense of what the IIIF manifest actually is. Humans don’t need this, having already found the object they can see what it is with their own eyes, assisted by clues from labels, descriptions, and other opaque strings carried by the manifest for display to the user. An agent harvesting IIIF manifests for the purposes of indexing or discovery can’t determine things like subject or creator from the manifest itself; it needs something it can understand at the other end of at least one linked seeAlso.

The manifest links to web pages and other human-readable resources about the thing it represents using the related property. These are links for humans to follow, that a viewer could show in its user interface. A typical example of related is to provide a link to the catalogue page for an object, so that wherever the object finds itself being used there’s a way of getting to the publisher’s preferred web page for that object.

The linked-to resources can point back to the manifest as well. Web pages can link directly, optionally using a recognisable icon and constructing the link so that it can be dragged-and-dropped into a compatible IIIF viewer. Descriptive metadata at the other end of a seeAlso can link back to the manifest using commonly understood vocabulary:

The third “I” in IIIF stands for Interoperability. Does that mean that, with all these institutions publishing their interoperable IIIF content, we have a magic bullet: a common format that cultural heritage institutions can use to publish and exchange metadata about their objects? Is IIIF, by the back door, a de facto lingua franca for cultural heritage interoperability?

No.

It means that you can see and annotate all these objects, which is a huge win. It’s liberating for content and application development to have a common format for viewing and annotating objects. But your model is still your model. You’re not going to persuade everyone else to adopt that. The descriptive metadata on the other end of seeAlso links can be just as diverse as before, representing individual institutions’ views of the world, their cataloguing practice and conventions.

However, there is an incentive to offer a chunk of descriptive metadata at the other end of at least one seeAlso that can be understood by as many potential machine consumers as possible, so that harvesters, aggregators and search engines can make sense of your manifest and index it properly. If you can manage to include some schema.org description of your objects for SEO purposes on your catalogue item web pages, you can link to a schema.org description from a seeAlso in the manifest for search and discovery purposes. There is more on this in part 4, Search and Discovery (coming soon).

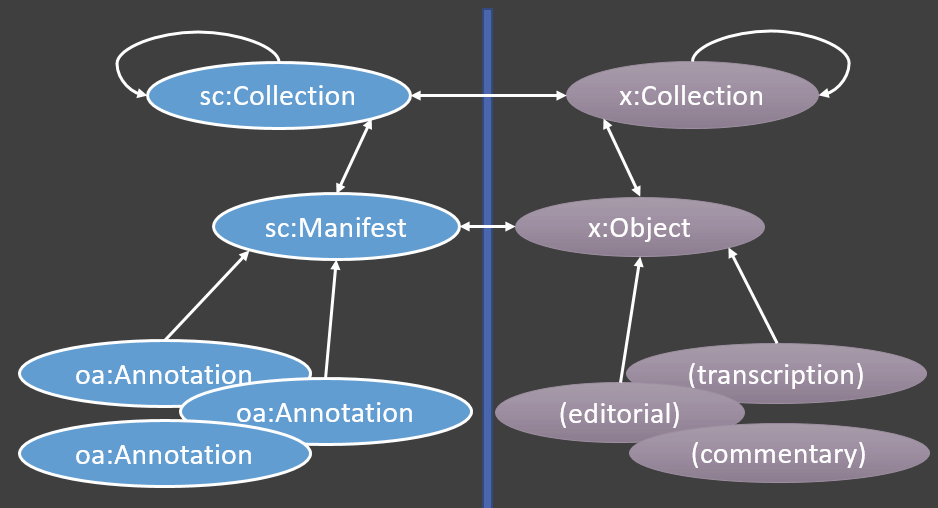

To build applications and services and share IIIF resources at scale, we need more than the twosome of descriptive metadata and IIIF manifest, with their links to each other. We need to aggregate IIIF manifests, and we do that with a IIIF Collection.

A Collection can be used to group manifests into a logical set. A three volume work could comprise three IIIF manifests, the Collection keeps them together. In the example of the periodical above, the catalogue record relates to a IIIF collection, rather than a manifest. In fact it relates to a collection of collections, as the structure can be as deep as you like. A collection can represent the entire periodical, the collection is composed of further collections each representing a volume, each volume is composed of manifests each representing an issue.

A collection can be used to group IIIF manifests and collections for any purpose:

All those reasons for grouping come from the way your content is modelled, or from editorial and curatorial intent, or from user intent. The collection itself has no semantics for why it is a collection; it’s just a shelf, or more accurately, a means of delivering a set of things to a client application, for whatever purpose. Those semantics must come from outside IIIF, from your application functionality, information architecture, and cataloguing practice. From your model.

A collection is for any purpose that requires aggregation of objects that humans can see (as opposed to aggregation of descriptive metadata resources or API objects). A collection can be as big as necessary, and can be paged for easier delivery to client applications. A collection can offer a search service.

You can publish a “top level” IIIF collection, a starting point that links to further child collections, and then eventually at the leaves of the tree, to manifests. This enables exploration of your IIIF resources by humans and machines, and could be used to drive web presentation too.

How does this fit into your model? A IIIF collection is for IIIF resources, so if your things are digitised they can be members of a IIIF collection. A IIIF collection cannot contain something that isn’t digitised, that isn’t either another collection or a manifest. They need to be objects for humans to look at. Just as IIIF manifests sit alongside your model and its descriptive metadata and don’t replace it, IIIF collections cannot replace any aggregation or hierarchy required for non-presentation purposes. Consumers of IIIF collections can only deal with IIIF resources as members, otherwise there’s no interoperability.

This is not a limitation, it would be a category mistake to try to aggregate descriptive metadata records in a IIIF collection. You can’t ask for trolley to be delivered from the stacks, and for books out on loan, instruct that the MARC record be placed on the trolley shelf instead of the actual book. The MARC record isn’t a tangible thing that can be placed on a shelf. This means that a IIIF collection hierarchy sits alongside other routes to objects and doesn’t replace them, just as manifests don’t replace catalogue records. The collection is part of the Presentation API, it’s only for things that can be presented.

In IIIF, all content is associated with a canvas (or with a manifest, collection or range) by annotation. The image annotates the canvas, but so do transcriptions, comments, links to blog posts and any other content. This is the third area where content from your model could be expressed in IIIF so that it is carried with the object and made available to applications.

Sometimes annotations are user generated content, notes, tags and comments contributed externally. But as far as IIIF is concerned it is all interoperable content, wherever it comes from - a web content management system, an annotation server, OCR data files, an electronic concordance. If you can map it across from your model, then it can go out into the world in interoperable form, carried by the Presentation API.

If you have content as part of your model (in the loosest sense) that would be useful to anyone who sees your IIIF manifest, then publish a link from the manifest, or the individual canvas, to an annotation list that links the object, or parts of the object, to the content through annotation.

This is examined in more detail on part 3, Annotations: How IIIF resources get their content .

Traditionally, digitisation happens after cataloguing. An existing collection is chosen for digitisation, and its catalogue records find themselves repurposed; labels and descriptions written decades ago surface in viewers and on web pages. An object was in the hands of cataloguer, the record was created. Years later, the object is photographed, additional structural metadata generated, and the object ends up viewable on the web.

IIIF offers an interesting alternative workflow, that could be brought to bear on mile after mile of shelved archival material that may be rudimentarily described at best. The material can be digitised before it is catalogued or described. Digitisation at large scale is a process that humans and machines together can do quite quickly. If the material is robust enough, and the intent is not to capture the finest possible image of each possible view, then a rapid work rate can be maintained.

This approach is not recommended for the world’s greatest cultural treasures, but if large numbers of images are captured and organised very generally into manageable units, then software tools can be used to sort the material.

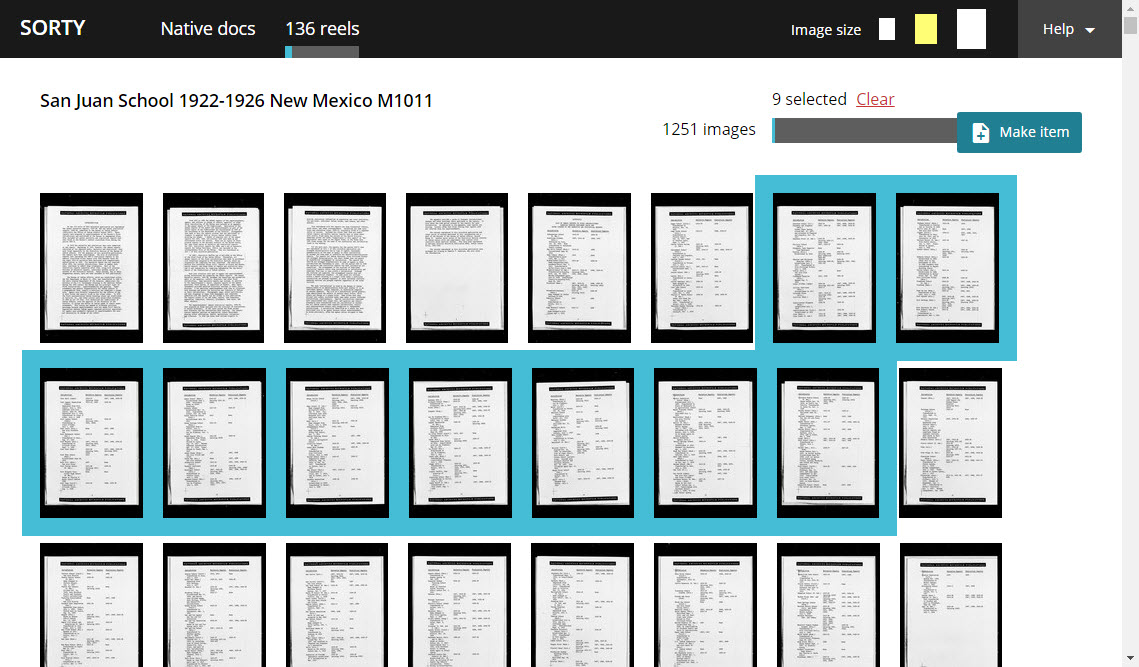

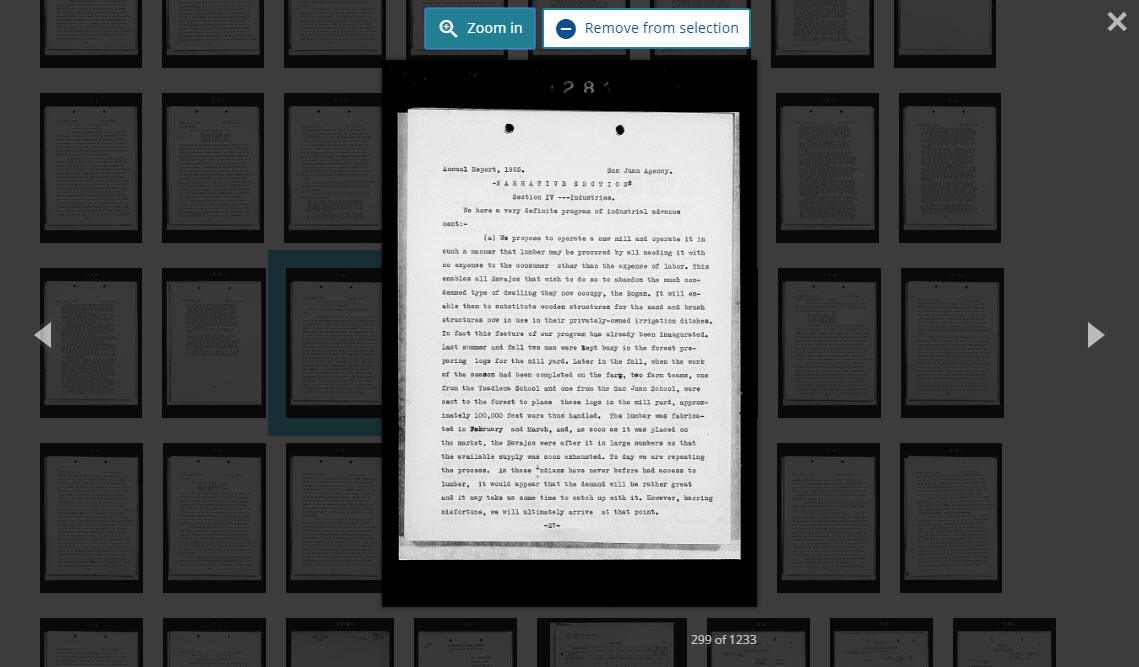

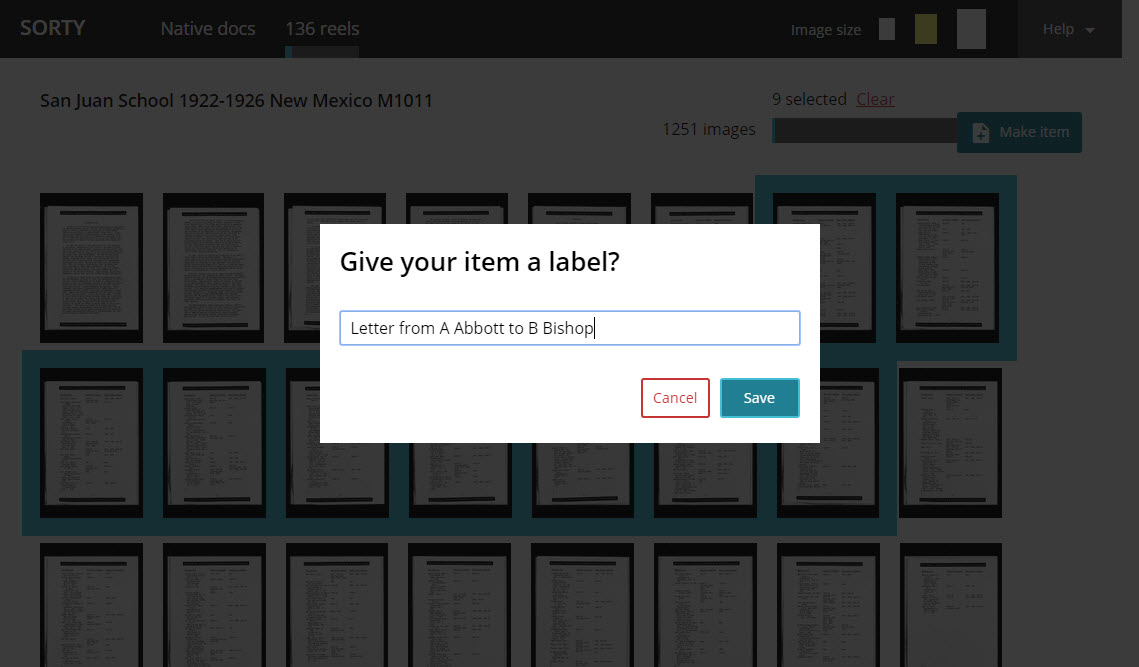

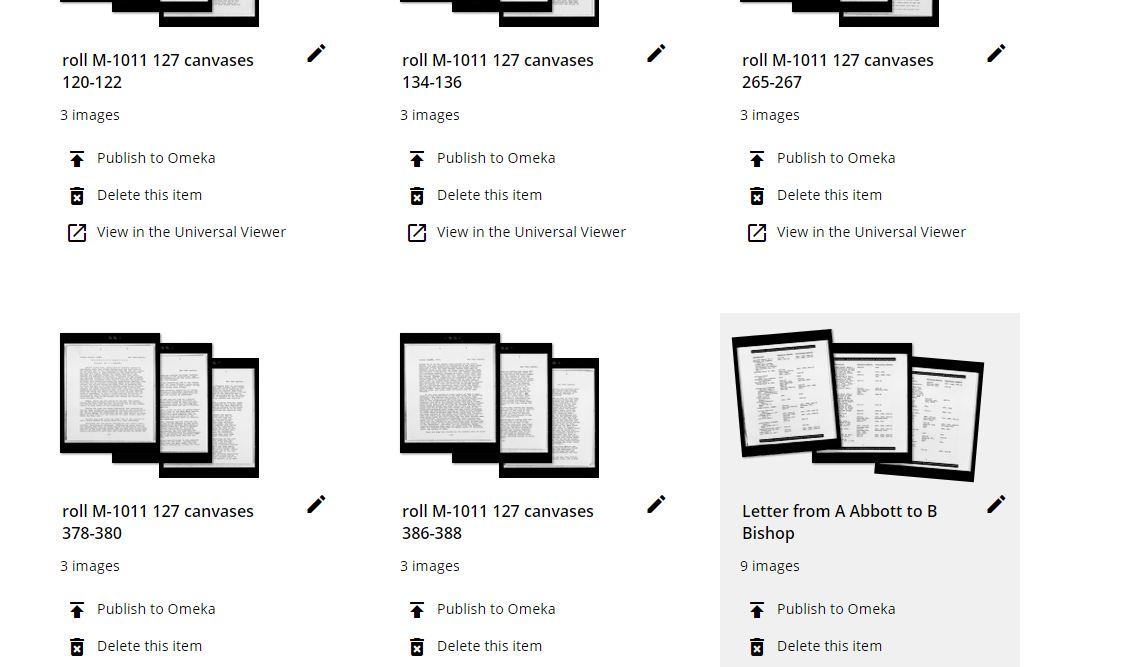

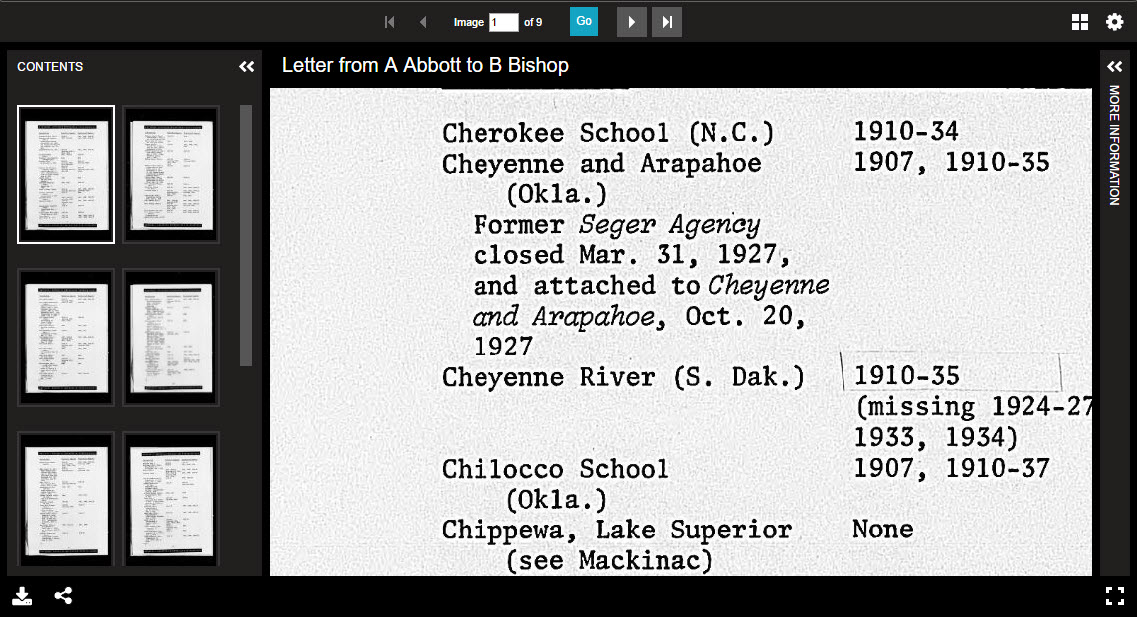

An example of this approach is the Indigenous Digital Archive project, where the raw material is digitised microfilm rolls, each of 1000 or so images. Each roll is digitised and a skeleton IIIF manifest generated. This is quite large, but not so large that general purpose viewers can’t handle it. A volunteer can load a manifest into the “sorting room” tool, and identify sets of images that should be individual objects - a letter, a report, a set of photographs. Once identified, the volunteer creates a new IIIF manifest from the selection, adds some metadata, and pushes the manifest into a collection management system, where an empty archival record is created.

The volunteer, or others that come later, can then start annotating the IIIF resource - tagging with people, writing a description, relating to other entities. Over time, more annotations accumulate. Eventually the annotations can be used to generate catalogue records.

IIIF is not being used to store this emerging model, but it is the mechanism through which new knowledge is added. It’s the digital equivalent of putting the object in the hands of the cataloguer, except that it’s a lot easier to sort through images on screen than laid out on a table, and we can assist the tagging and identification process with a battery of machine learning processes including OCR, entity recognition, image analysis, handwriting recognition and various text processing tools that work on machine-extracted text.

We can use existing tool chains - viewers, annotation applications, annotation servers - to assist us with cataloguing. The IIIF manifest comes first and allows people to see the object as an object for the first time. The descriptive metadata emerges once the object is viewable.

Selecting an object in a microfilm roll of 1251 images

Going in for a closer look

Giving the object its most minimum amount of metadata

Now it exists as a IIIF manifest

...and can be seen and shared in a viewer

More Digirati updates